An occasional series where I watch and review works inspired by Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula…

These reviews reveal plot twists.

Faithful to the novel? Based on the Marvel character of the same name, who had only debuted in the comic books a couple of years earlier, animated TV series Spider-Woman follows magazine editor Jessica Drew, who tackles a variety of villains and monsters using an arachnid alter ego.

In lieu of an introductory episode, we’re told the backstory during each week’s opening titles. When Jessica was a child, she was bitten by a venomous spider, so her scientist father injected her with an experimental antidote (‘spider serum #34’), which saved her life but also gave her superhuman abilities… While ‘weaving her web of justice’, Jessica (now an adult voiced by Joan Van Ark, later of Dallas and Knots Landing) can fly, thanks to web-wings on her red-and-yellow spider-suit, as well as stick to walls and ceilings and shoot ‘venom blasts’ out of her hands. When not in her superhero persona, she’s a hotshot editor who runs Justice Magazine; her closest friends are photographer Jeff Hunt (Bruce Miller) and her young nephew Billy (Bryan Scott).

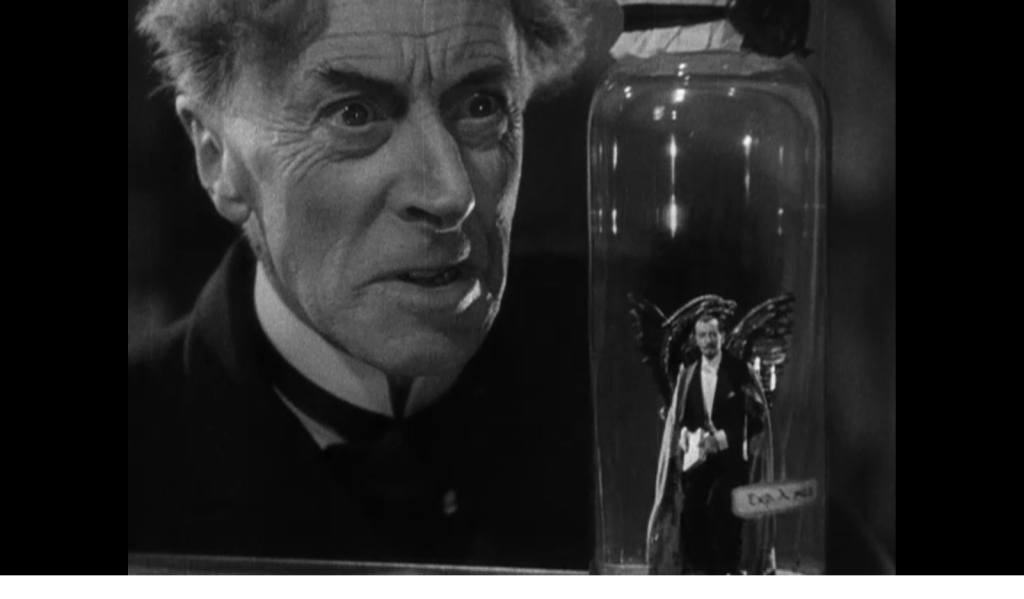

The show’s connection to Dracula comes in the 10th episode, Dracula’s Revenge, which was originally broadcast on 24 November 1979. In a spooky graveyard, two grave robbers resurrect the vampire Count Dracula who has been entombed for 500 years. He is very much the Dracula cliche: Romanian accent, fangs, goatie board, red-lined cape, the ability to turn into a bat. Before he was defeated five centuries earlier, the Count put a curse on the family of his rival Van Helsing, and now he’s back he seeks out the rival’s descendent – who bizarrely lives in Castle Dracula – so he can turn him and his friends into vampires.

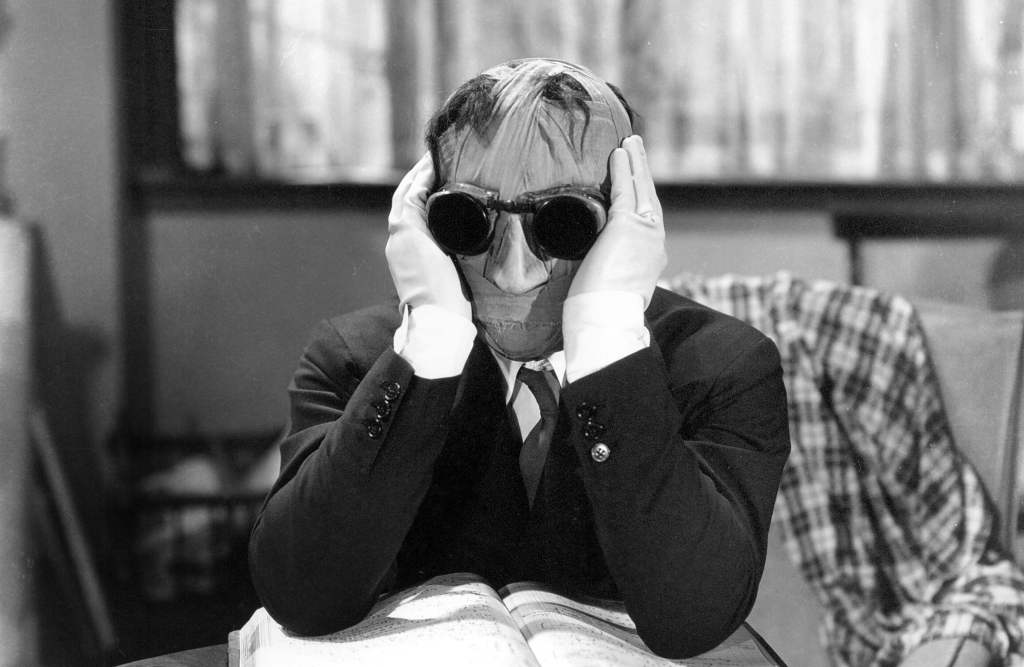

Thankfully, Jessica somehow intuits the danger – even though she’s several thousand miles away – and heads over to Europe with Jeff and Billy in tow. Dracula, meanwhile, also resurrects two allies: the Wolf Man and a very Boris Karloff-like Frankenstein’s Monster. Jeff and Billy are soon turned into monsters, and then Spider-Woman begins to metamorphose into a half-vampire, half-wolf hybrid. But thankfully she’s able to do some quick library research into the creatures and, one-by-one, squash the threats.

Setting: The modern day (late 1970s). Jessica and her pals live in an unnamed US city, presumably New York, and we see them attending a local cinema to catch a horror film. But the bulk of the action takes place in Romania. Jessica travels there at first via her superhero ability to fly, but when she has to return later accompanied by Jeff and Brian they use the Justice jet-copter.

Best bit: Given that Spider-Woman was a children’s show, the way Count Dracula converts victims into the Undead had to be changed, of course. So rather than seduce people and drain their blood, this version of the character shoots green laser beams out of his hands and this somehow results in them becoming vampires. No sex please, we’re a kids cartoon.

Review: Created for television by genre legend Stan Lee, the animated series Spider-Woman only ran for 16 episodes. In that time the lead characters encounter a myriad of flamboyant threats – a resurrected Egyptian Mummy, a demon, time-travelling Vikings, urban criminals, dinosaurs, a giant spider, androids, aliens – but neither Jeff nor Billy ever learn that Jessica is a superhero. In the standard format of these things, they just don’t spot that Jess goes missing as soon as Spider-Woman swings into view. (Dracula’s Revenge actually contains a sly joke about this: Jessica is forced to switch into her Spider costume in a phone box – a deliberate nod to fellow hero Superman. ‘Well, it’s not exactly my style,’ she says to herself, ‘but it’ll have to do.’)

It all makes for a diverting adventure series that features some whimsical threats and doesn’t outstay its welcome. The use of Dracula is part of a long tradition of the vampire count cropping up in cartoons for children – see also Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends, Scooby-Doo, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and more – and while the drama of the situation never approaches anything too complex, the writers have fun hinting towards the cliches. But the series’ most appealing aspect is the fact Spider-Woman is a quietly progressive cartoon series. For one thing, it was the first animated superhero show to focus on a female character; for another, Jessica is a successful professional who doesn’t bat her eyelashes at any of the male characters. Maybe that’s what riles the famously misogynistic Dracula the most.

Six monster pictures (they give me nightmares) out of 10