I’ve set myself the challenge of watching all 28 films from Universal Studios’ golden age of horror that feature Count Dracula, Frankenstein’s Monster, the Mummy, the Invisible Man, the Wolf Man and the Creature from the Black Lagoon…

Spoiler warning: these reviews reveal minor plot points

Bela Lugosi’s name was made playing Count Dracula, initially on stage for two years then in Universal’s movie adaptation in 1931. His interpretation – the halting Hungarian accent, the languid demeanour, the dinner suit and cape – became the definitive Dracula and raised the actor to the status of a horror star. But he didn’t play the part again on film for 17 years.

Instead, his 1930s and 40s were dominated by Gothic, spooky and scary characters in non-Dracula horror films, amongst them Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932), White Zombie (1932), Island of Lost Souls (1932), Mark of the Vampire (1935), The Raven (1935) and The Dark Eyes of London (1939). He also cropped up a few times in the Universal Monsters series. In 1939, he played the grotesque henchman Ygor in Son of Frankenstein; in 1941, he cameoed as a gypsy with a secret in The Wolf Man. Despite Dracula being his most famous role, it’s in these other films where you best see Lugosi’s talent for injecting empathy and soul into macabre, off-kilter characters.

He was given perhaps the best opportunity to shine when Universal chose to focus on Ygor for their follow-up to Son of Frankenstein. Although created for Son of…, the sidekick was essentially the same character as the hunchbacked Fritz played by Dwight Frye in the studio’s first Frankenstein film. Fritz was not taken from Mary Shelley’s novel – he was added to the mythology for a 1823 stage adaptation – but this run of films cemented the idea of a deformed, uneducated yet loyal aide to a powerful villain. Throughout the 20th century and beyond, this trope-character has been used in myriad films and TV shows – House of Frankenstein (1944), House of Dracula (1945), House of Wax (1953), Jesse James Meets Frankenstein’s Daughter (1966), Dracula vs Frankenstein (1971), Young Frankenstein (1974), The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), The Halloween That Almost Wasn’t (1979), The Munsters’ Revenge (1981), Count Duckula (1988-1993), The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), Van Helsing (2004), Igor (2008), Victor Frankenstein (2015) and countless more.

The Ghost of Frankenstein, which has precious little connection to Mary Shelley, begins with a prologue set soon after the previous film. Local villagers, fed up with the misery brought to the area by the Frankensteins, attempt to destroy the family castle. However, their actions accidentally resurrect the Creature, much to the delight of Ygor who has been keeping vigil over his friend’s resting place while playing a mournful tune on a horn. After being brought back to life, the Creature is initially weak, though thankfully he gets struck by lightning during a storm and this peps him up. ‘Your mother was the lightning,’ says Ygor, referring back to the character’s creation. ‘She has come down to you again.’

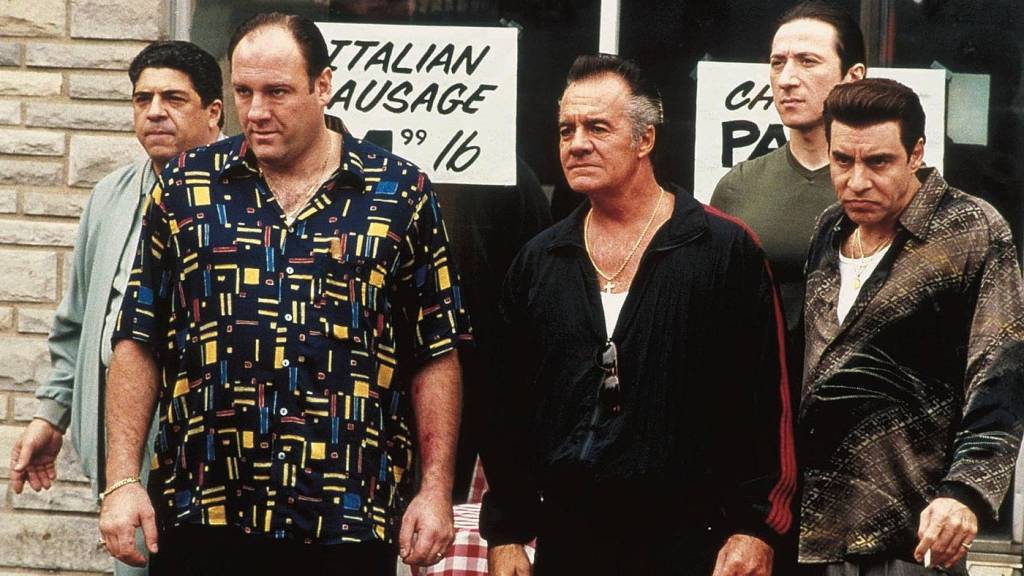

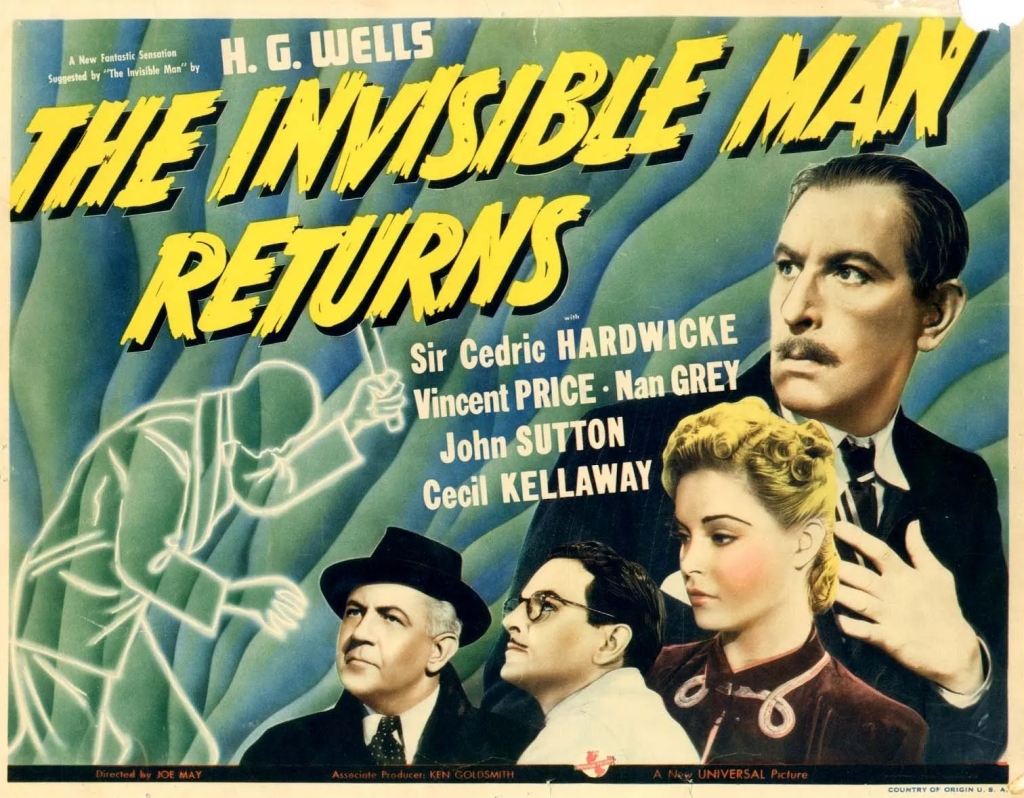

The pair resolve to seek out Baron Frankenstein’s second son and ask for help. Arriving in the town of Visaria, the Creature befriends a small girl – a deliberate nod to the first Frankenstein film‘s most infamous scene – but is arrested after killing a villager he thought was being antagonistic. Meanwhile, we meet Dr Ludwig Frankenstein (Cedric Hardwicke, The Invisible Man Returns) who has just carried out a revolutionary brain operation at his medical practice. He lives with his grown-up daughter, Elsa (The Wolf Man‘s Evelyn Ankers), while her beau is the local prosecutor, Erik (Ralph Bellamy, another The Wolf Man alumnus). After the Creature’s arrest, Erik asks Ludwig to assess the prisoner ahead of a trial. Oddly, they all just treat the Creature as if he were a madman; no one seems to notice he’s a stitched-together cadaver brought to life artificially. But then Ygor appears and blackmails Ludwig into helping him – the doctor doesn’t want the locals knowing about his family’s macabre history.

Elsa is also in the dark about the backstory – that is, until she finds the Frankenstein family papers. As she reads them and is aghast at the actions of her grandfather (Frankenstein and Bride of…) and uncle (Son of…), we’re treated to flashbacks from the earlier movies. Ludwig, meanwhile, is feeling the pressure. He wants the Creature euthanised, but his assistant Bohmer (Lionel Atwill, who had played a different role in Son of…) refuses to assist with the operation: ‘It’s murder!’ he cries. Ludwig therefore decides to go ahead alone. His conscience starts playing tricks on him now and he sees visions of his father’s ghost, who argues that the Creature’s criminal impulses could be cured… by swapping its brain with someone else’s! Cedric Hardwicke doubles up to play the spectral role, even though we’ve *just* seen original Henry actor Colin Clive in the flashbacks, and there is a clear echo of Hamlet here with the conflicted son given fatherly guidance from the afterlife. When the Creature realises what Ludwig has in store, he wants his brain replaced with the little girl’s. But Ygor and Bohmer overhear and conspire to swap it with Ygor’s instead…

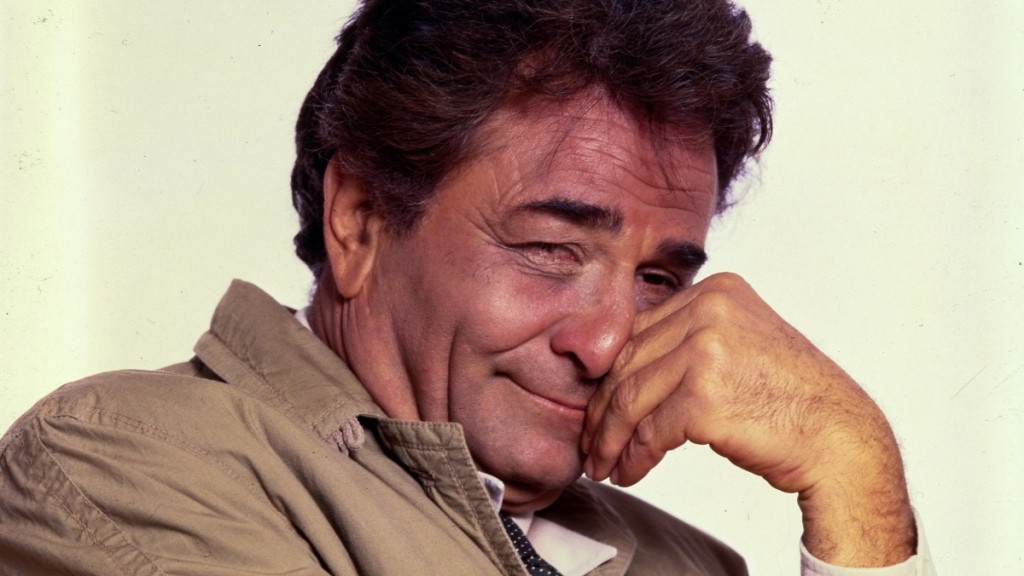

After his trio of appearances as the Creature, Boris Karloff was unable to reprise the role this time (he was busy starring in Arsenic and Old Lace on Broadway). So in his place director Erle C Kenton cast the rising star of the Universal stable – the 6’2″ Lon Chaney Jr, fresh from his success in The Wolf Man. Sadly, rather than capture the inner sadness and sympathy that Karloff had found, Chaney gives a lumbering, vacant performance. Frankly, anyone could be behind the make-up. Elsewhere, Hardwicke, Bellamy and Ankers – the latter two playing similar characters as those in The Wolf Man – all fail to make an impression. In fact, almost the entire cast play their scenes in a blandly straight way. It’s melodrama without the heightened emotions, while Kenton directs as if he’s keen to get home that day. Bela Lugosi’s enjoyably theatrical performance is left to add the fun and ghoulishness.

Five secrets of life artificially created out of 10

Next: It’s war!